Imagine you are forced to go to a hospital to receive psychiatric treatment that you don't think you need. What rights would you have?

That's the question at the heart of a legal battle between the state of New Hampshire and the American Civil Liberties Union.

The case has big implications for New Hampshire, but it also highlights a nationwide problem: A shortage of mental health beds is leaving patients stranded in emergency rooms for days or weeks at a time.

Anxiety and agitation

Meme is 61. She works for an organization that helps people with disabilities.

Meme is a family nickname. NPR is not using her real name because she is afraid of the discrimination that might follow someone who has been involuntarily committed for a mental illness.

In September 2018, Meme was suffering from severe stress and anxiety.

"It was just the perfect storm of stressors," said Meme, "so I'd taken the day off and I was recovering at home."

Later Meme's adult daughter arrived at her house. She was alarmed by Meme's condition. She later described it as a "psychotic break." But Meme didn't think she needed any help. They argued. Then Meme's daughter called 911. When local police arrived, they found Meme agitated and erratic, according to a police report. They told her she had to go to the hospital. Meme refused.

"I definitely did not need to go," said Meme. "I did not want to go."

Finally, according to the police report, an emergency medical technician instructed police officers to hold down Meme's arms.

"And the next thing I know, they're stabbing me in the arms with some kind of sedative," said Meme. "Stab, stab. Next thing, I'm waking up at St. Joseph Hospital."

Meme awoke in the emergency room of St. Joseph Hospital in Nashua, N.H. She wanted to leave. But the hospital wouldn't let her because Meme's daughter and an emergency room doctor filled out a legal petition that said Meme was a danger to herself or others because of a mental illness.

After one of those petitions is filed, according to New Hampshire law, patients like Meme should be transferred out of the ER to a psychiatric care facility. They should also get a hearing before a judge within three days. That would be Meme's chance to argue that she should not be held against her will.

But there's a problem.

The psychiatric facilities in New Hampshire are all full. On any given day, there is a waitlist of around 35 people. And those hearings at which Meme could argue to a judge that she should be allowed to go home — those are held only at those psychiatric facilities.

The result: Meme couldn't leave the ER, and she couldn't get a hearing. Not until a bed opened up.

"And they won't even tell you what number you are," said Meme of the hospital staff. "You ask every day, 'What number am I?' 'Oh, we don't know.' "

Going home

The legality of this situation is now being debated in federal court. The question is not whether Meme should've been forced to come to this emergency department in the first place; it's whether her rights were violated once she got there.

Meme ended up spending 20 days locked inside a wing of St. Joseph's emergency department. She says that her access to visitors, the telephone and the bathroom were limited and that hospital staff concerned about her committing suicide restricted what objects she could have.

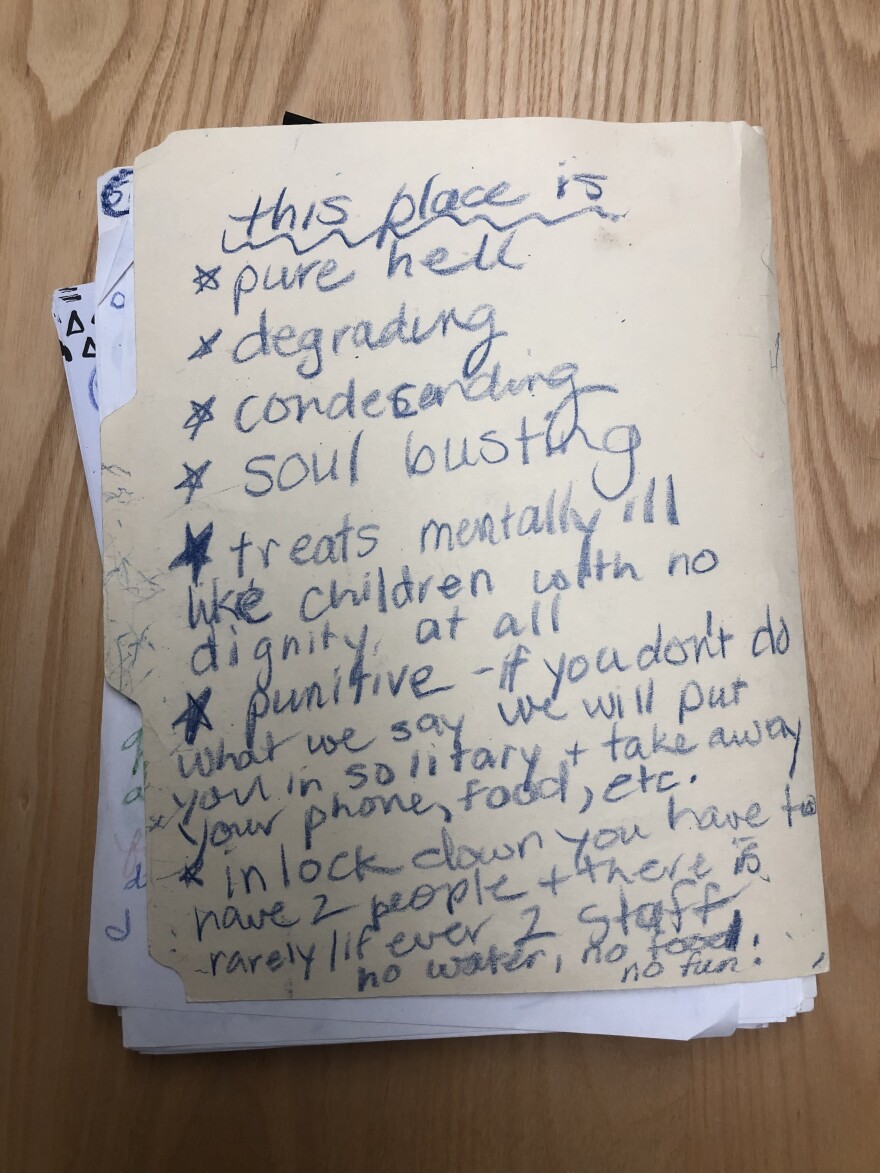

"During my stay, to help keep me sane, I took notes with a crayon and coloring paper, because that's the only thing I was allowed to have to write with," said Meme.

A spokesperson for St. Joseph Hospital wouldn't comment on the specifics of Meme's experience. But in a legal filing, the hospital denies any allegations that the conditions of Meme's stay were poor.

After 20 days in the ER, Meme was finally transferred to a psychiatric care facility. Two days later, she received her hearing.

"You get your husband to bring you your finest dress," said Meme, "and you go in there. You get a lawyer who's assigned to you."

In the end, Meme didn't even have to argue that she should be released. Meme's daughter, who had written the petition to involuntarily commit her, didn't show for the hearing.

Meme was released. For the first time in more than three weeks, she got to go home.

Now Meme is one of a handful of plaintiffs being represented by the ACLU of New Hampshire in a federal class action lawsuit against the state for not providing that hearing to her sooner.

Nationwide problem

The lawsuit is just one symptom of a nationwide problem: a shortage of mental health treatment options, including inpatient beds.

"That particular issue affects almost every emergency physician in almost every emergency department across the country on a daily basis," says Dr. Enrique Enguidanos with the American College of Emergency Physicians.

Enguidanos says that many ERs are overwhelmed by an influx of psychiatric patients who have nowhere else to go. In a recent American College of Emergency Physicians poll, 70% of ER doctors reported that they were boarding psychiatric patients.

Enguidanos says that when he is treating a patient with a heart attack, national guidelines say he should stabilize that patient and then transfer the patient to a cardiologist as soon as possible.

"And we do that well. We do that within 30 minutes across the country," said Enguidanos.

For psychiatric patients, the wait can be days or even weeks.

Copyright 2021 New Hampshire Public Radio. To see more, visit New Hampshire Public Radio. 9(MDAxODg3MTg0MDEyMTg2NTY3OTI5YTI3ZA004))