There’s been a lot of attention focused on Baltimore’s youth in the year since Freddie Gray died. And much of that spotlight has been on Frederick Douglass High School. Images of dozens of Douglass students throwing rocks and bottles were captured on TV as protests turned violent the day of Gray’s funeral. As part of our series, Baltimore: A Year after Freddie Gray, we look at how Douglass students are trying to take control of their own story.

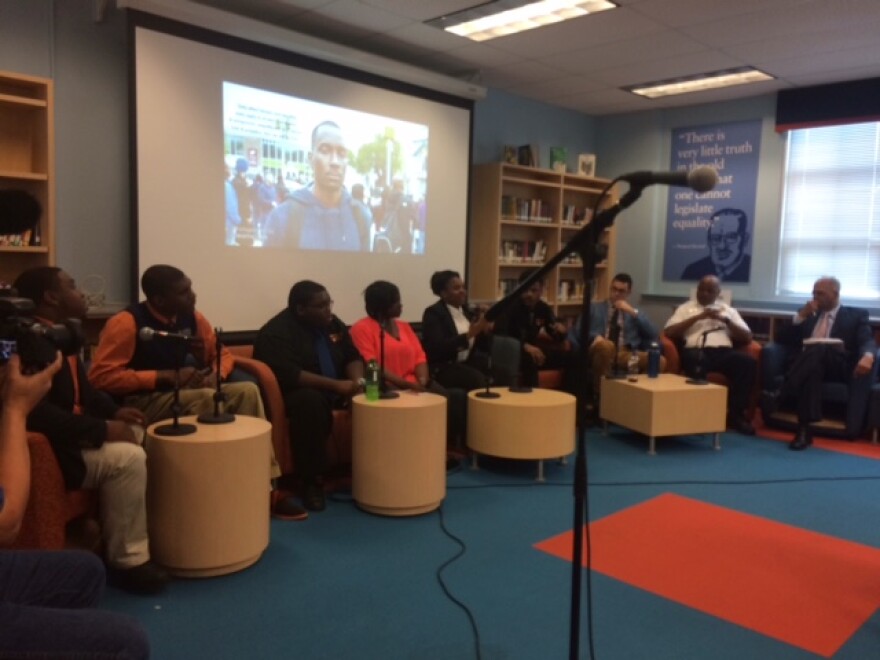

Douglass students, their teachers and a group of reporters crammed into the school library on Wednesday to field questions about how the school has changed since Freddie Gray. Several students, two teachers, a school police officer and City Schools CEO Dr. Gregory Thornton, sat at the front of the room. Behind them were scrolling images of Baltimore residents photographed on city streets. A scrum of cameras from local TV stations filmed from behind the audience.

The first questions came from the students.

"My question is how have the students at Frederick Douglass High School been able to overcome the expectations of society since the incident?," asked a senior.

De’Asia Ellis, a senior, who plans to attend Goucher College with a full scholarship next year said she’s seen personal growth among her fellow students since last year’s rioting.

"I think it opened up our eyes to see we can’t be suppressed; we can’t be that stereotypical person that everyone thinks we are," she reflected. "We have to rise above what people think we are or their perceptions of us. And I think a lot my peers understand that a bit better after the riots because they heard a lot of different opinions that people put on us."

And junior Dominick Carter bristled at a question from Channel 11’s Lisa Robinson, who asked what students would say to people who blamed them for the unrest and violence.

"I’m so sick of hearing that. Whoever said that, that’s a huge, egregious lie." He said the events last year were like a scar from riding a bike: at one point you learn how to ride a bike and the scar fades. "That was one of those little marks and scars you grow up as a kid that we don’t need to keep being branded with. We get it, it happened, let’s move on."

The students showed a mix of frustration with the news media and weariness from a year of being thrust into the spotlight. From their answers, it was clear they want to regain control of the narrative of what started the unrest and what it’s like to grow up in the inner city. Senior Uriel Gray said his peers are living in distressed neighborhood under circumstances that are no fault of their own.

"I’m 19 years old. My community was already destroyed before I came out the womb," he said as the crowd murmured in response. "I grew up in certain places where I would have abandoned houses to the right and the left of me. I don’t have any control of that. I can’t rebuild a house. I’m here to get an education so I can learn that kind of thing."

They talked about holding people accountable for the events of April 27th. Like why were the subway and bus routes shut down at Mondawmin Mall that day, leaving students trapped, along with hundreds of riot police? The answer still isn’t clear.

Teachers pointed to larger issues within the school system like a curriculum in need of an update so it’s more relevant to the issues students are facing now. And one student said the school still needs news books, computers, chairs and desks.

It isn’t that they weren’t offered help. Last year retired Ravens linebacker Ray Lewis came with his teammates; so did NBA star Carmelo Anthony and rapper Wale. But as Dominick Carter tells it:

"People came up here post-riot. Those two months after the right Douglass was hot. What do you need? What’s this that and the third. We got you all. And then we ain’t never seen them again."

And the football field still doesn’t have lights.