Eighteen years ago, Maryland was gripped by the Pfiesteria crisis. Governor Parris Glendening closed off parts of three Eastern Shore rivers because of reports that a toxic micro-organism – Pfiesteria piscicida -- was causing fish kills and memory loss in watermen.

Headlines in The Washington Post headlines warned of “the cell from hell.” Panic drove down sales of Chesapeake Bay seafood. The source of the outbreak: manure from Eastern shore poultry farms that fed toxic algal blooms.

In the nearly two decades since then, the manure runoff problem has continued and even worsened. But no more fish kills or illnesses have been attributed to Pfiesteria, which seemed to vanish as inexplicably as it appeared.

So what happened? Was Pfiesteria just a bad dream? There is growing evidence that the Pfiesteria frenzy was a case of scientific error that triggered an over-reaction by government, journalists, and consumers.

The research of Allen Place, a biochemist with the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science, has concluded that the state government blamed the wrong organism for 1997 fish kills. Place said his investigation points to a different microorganism called Karlodinium veneficum. “Karlo” is an algae that is quite common every summer in the bay but does not pose any threat to human health, beside skin irritation. Karlodinium can be found even today in the waters of Baltimore’s Inner Harbor.

Place stood beside the harbor on a recent afternoon, near his lab at the Institute of Marine and Environmental Science, pointing into the murky water.

“We’re next to the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Taney, in one of the slips next to our building, and this kind of greenish, sort of pea colored water is normally an indication of karlodinium,” Place said.

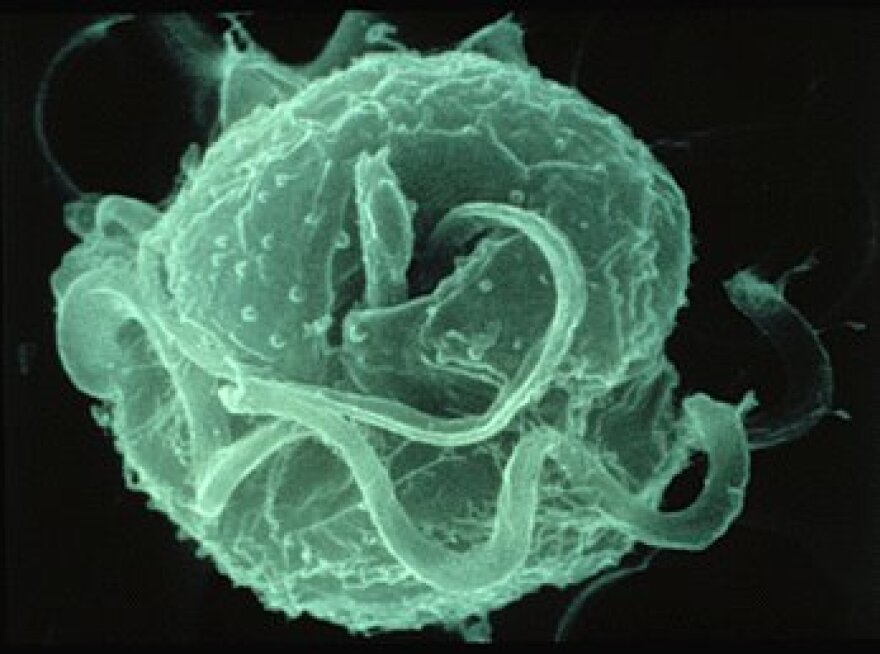

He explains that Karlodinium and Pfiesteria are very similar looking one-celled organisms – tiny balls with dual whip-like tails -- that are easily confused under a microscope. But Place said his research shows that Pfiesteria (despite its killer reputation) does not produce toxins.

“For many reasons, I don’t think Pfiesteria has the capacity in nature to kill fish,” Place said. “It will eat dead and dying fish – or dead and dying anything.”

Wolfgang Vogelbein, a biologist at the Virginia Institute of Marine Science who helped to study the 1997 fish kills, said that he also no longer believes the original narrative about the Pfiesteria crisis. “It was claimed that Pfiesteria was the cause of these massive fish kill events, and that there were human impacts, that fisherman were being impacted. And we’ve pretty much put that whole story to rest," Vogelbein said. "That turned out to be some poor science. As it turns out, (Pfeisteria) is not even a toxin producer.”

These conclusions are not accepted by all scientists. The originator of the Pfiesteria theory, JoAnn Burkholder, a professor at North Carolina State University, still maintains that Pfiesteria did cause at least some of the fish kills in 1997.

Burkholder theorized that there have been no fish kills caused by Pfiesteria in the Bay since 1997 because the organism may require unusual weather conditions (very still, hot conditions) to release toxins, and these conditions have not re-occurred in the last 18 years.

“Frankly, I think Pfiesteria is very sensitive to weather conditions and not nearly as tough as some of the other harmful algae,” Burkholder said.

What may have triggered the symptoms of illness among two dozen watermen in 1997 remains mysterious.

A study funded by the National Institutes of Health from 1999 to 2002 found that Pfiesteria is actually common in the Bay’s waters but harmless to people. Long-term examinations of the health of 107 Chesapeake Bay watermen found that their frequent exposure to Pfiesteria in the water not cause any memory loss or any other health problems.

“Bottom line: We found no correlation between work (by watermen) in areas where Pfeisteria was identified, and specific symptoms or changes in neuropsychological tests,” said Dr. J. Glenn Morris, the former director of the University of Maryland School of Medicine’s Pfiesteria research program. “We did a whole lot of studies trying to figure this out… and based on the data we got, I feel very comfortable that the bay is safe,” said Dr. Morris, who is now director of the University of Florida’s Emerging Pathogen Institute.

In contrast to Pfiesteria, Karlodinium is a very well documented producer of toxins. These poisons have been the cause of numerous fish kills in the Chesapeake Bay and around the world since 1997 (although not sicknesses in humans.)

“We know that Karlodinium is a fish killer,” said Patricia Glibert, a biologist at the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science. “We know that Karlodinium may have contributed to fish kills that were observed in 1997…. It certainly is an organism of great concern in the bay.”

Karlodinium blooms in the bay increased six-fold from 2003 to 2008, from fewer than five per year to more than 30 per year, according to a recent scientific paper published in the journal Harmful Algae by Glibert and colleagues.

This increase is likely to continue a warming climate and more nitrogen and phosphorus pollution combine to breed more harmful algal blooms, Glibert said. Also increasingly common in the bay are algae called Prorocentrum minimum, which cause a phenomenon called mahogany tide. Blooms of mahogany tide have doubled in the Chesapeake Bay over the last 20 years.

Looking back, Pfiesteria turned out to be not the “cell from hell” – and not even a big deal.

But nitrogen and phosphorus pollution, including from poultry manure, is causing a multiplication of toxic algal blooms of other species. And the increases in these other varieties of harmful algae – although not often discussed in the news media and so unknown to the general public – provides a justification for the government to require steep reductions in pollution.